Long ago and far away,

Far away and long ago,

The World was honeycomb, we know,

The Worlds were honeycomb.

Description:

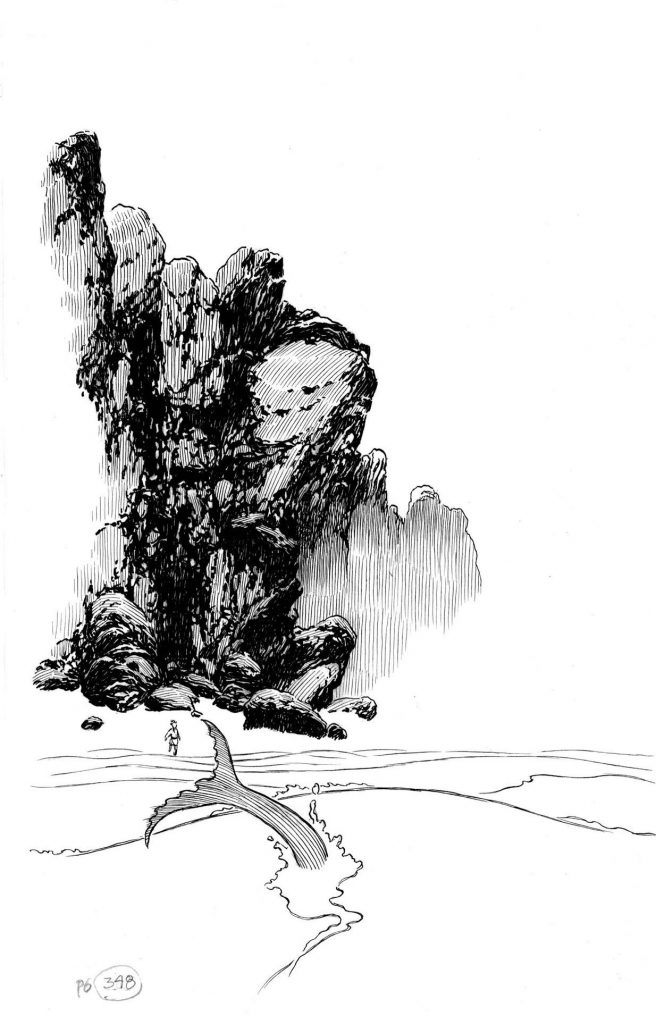

Eerie, dark and opulent, cocooned in silk and shadows, this is a novel unlike any other: a honeycomb built from a hundred cells, each cell a story in its own right. Gorgeously Illustrated by Charles Vess, it follows the tale of the Lacewing King, magical trickster and ruler of the Silken Folk; his misadventures, his treacheries and his pursuit through many Worlds by both the vengeful Spider Queen and the deadly Harlequin. On his journey through the Worlds of the Folk, of the Sand Riders, the Undersea, the River Dream and even the Kingdom of Death itself, he encounters a multitude of characters – a clockwork woman, a watchmaker’s boy, a huntress with a mechanical tiger, an undersea Queen in love with the Moon, a princess who dreams of a library – but none more magical than the bees, the little builders of honeycomb, taking their nectar of dreams to the hive, and spinning them into stories.

Background.

HONEYCOMB is a different project to anything else I’ve ever written. This is at least in part because of its construction; and because it was written in a completely different way to any of my other books, and via a different medium; that of social media.

I started to write these stories some years ago, on Twitter. Under the hashtag #Storytime, I would write them, live and from scratch, in front of a Twitter audience, whenever the spirit moved me, at odd moments during the day. I wrote them on trains; in airports; in response to current events; and because they were fables and fairy tales, I wrote them in a rather particular language, using the character limitation imposed by Twitter to create a deliberately stylized and performative manner of storytelling, closer to the oral tradition than to the written form. And I always began with the following phrase:

There is a story the bees used to tell, which makes it hard to disbelieve.

One of the most interesting things about social media is how intimate it feels. Telling stories on Twitter feels much more like a live performance than a merely written one. And little by little I began to understand that these pieces of ephemera – originally meant to be sent out on Twitter like seeds on the wind – were part of something larger; a world of returning characters and interconnected storylines, fitting together organically, like a piece of honeycomb.

I started to keep my stories, instead of letting them disappear. Many people asked me if I was planning to publish them. At the time, I had no such plan, but a couple were published in magazines, and one made it to an anthology, ambitiously subtitled “The 100 Greatest Short Stories Ever Written”, 2 years after the editor, David Miller first read it on Twitter. The same story also became a mini-opera, with music by Lucie Treacher (you can see the process of translating a short story to a libretto here, and there’s a link at the end to the final performance). I used several of my stories as a basis for a live music and storytelling show with the band in which I had played since I was in my teens – stories are naturally volatile, crossing naturally from one medium to another, and they translate well both to music and to illustration. After three or four years of #Storytime, I realized that I had already written over a hundred of these stories, some dark, some funny, some moving; some sad; all set in the same fictional multiverse as Runemarks and The Gospel of Loki, as well as that of Orfeia, The Blue Salt Road and A Pocketful of Crows. Some are only loosely interconnected, others are part of an overarching storyline that evolved naturally over the years to make, not a collection of tales, but a novel in the shape of a jigsaw puzzle made up of exactly one hundred chapters, each one a story in its own right, in which every story is a piece of the larger picture.

I started to toy with the idea of putting these pieces together to create an original, illustrated book for adults, in the tradition of the classic golden age of fairytales.

It took me some time to persuade Charles Vess to illustrate my stories. But I’d always loved his work, and I knew he’d understand what I was trying to create. There are so few fairy painters left who actually believe in fairies: and for this project, I needed someone who could recreate the magic in a different medium.

Read more about working with Charles.

This book is the result of that: a labour of love in so many ways, and a testament to the power of the oral tradition of storytelling. These are all new stories, and yet to me they feel intimately connected to those collected by Grimm and Perrault, or set out in the Child Ballads. Perhaps this is because such stories, like the ones in HONEYCOMB, are all part of a larger narrative; that of our shared experience, the story of our hopes and dreams.

I hope you’ll find yours there, too.

Thinking of making HONEYCOMB a part of a reading group discussion? Get your reading group guide here, including background info, questions for discussion and an easy honeycomb recipe….

More questions? Here’s a quick Q & A to get you started.

Q&A

Q: This feels quite familiar. And yet it feels new. How much does this book owe to Grimm’s fairy tales and the Child Ballads?

A: I owe a lot to our traditional folklore in terms of background, theme and style. I also owe a debt to The Thousand and One Nights, at least in terms of the book’s structure. But Francis Child and the Brothers Grimm were collectors of traditional tales. Their names are known because they transcribed folk stories and ballads from the oral tradition. Because all but one of the stories in HONEYCOMB are original, I feel I owe more to writers like La Fontaine and Anouilh, whose fables were often based on contemporary events and themes, but whose style took inspiration from the tales of the oral tradition.

Q: Why do you think we still need fairy tales in 2021?

A: For the same reason we’ve always needed them. Some things are easier to articulate and explain to ourselves through metaphor. We live in dark and difficult times; fairy stories help us to believe that our monsters can be defeated; that love can save us; that change is possible; that a kind of magic exists, and sometimes they even help us to laugh at the things that frighten us.

Q: Some of these stories are very dark. Would you say they’re suitable for children?

A: I think that’s up to the individual child. In my experience children are very good at knowing what will suit them. But I didn’t write them with children in mind, so if you’re buying this book for a child, feel free to discuss the stories and make sure they’re not upsetting.

Q: Did you ever take inspiration from current events for these stories?

A: Very often, yes. The King’s Cuckoo was written when J.K. Rowling was revealed to have been writing as Robert Galbraith; The Teacher, when Richard Dawkins made his derogatory remarks about fairytales. Some reflect things that were going on in politics, or in the world of publishing. Some came from personal events, or items I saw in the news. But that’s true of all stories; and to me it’s not really the birth of a story that’s the most interesting; it’s where the story can take you.

Q: I’m pretty sure some of these tales have a message or moral; I’m just not always sure what it is. Why didn’t you put in explanations, like La Fontaine’s fables?

A: I thought about including footnotes, and decided against. I prefer my books to ask multiple questions, rather than to provide just one answer; and I’ve realized that readers will interpret – and benefit from – stories in all kinds of very personal ways. I didn’t want to take that opportunity away from them. Besides, messages in stories change with time: what was written with a specific event in mind ten years ago may find a different relevance now.

Q: None of the characters in this book have names. Was that a choice?

A: Yes, it was. I wanted to give a sense of universality to the themes in these stories, which is why I’ve deliberately not given official names to countries, either. All of them take in the same multiverse I started to build in RUNEMARKS and THE GOSPEL OF LOKI – a universe of Nine Worlds, which has proved itself to extend over a lot more. Recurring elements, like the Night Train and the River Dream run through all these books, and are of my own invention, although concepts like the Land of Death, or the World of the Fae are already very familiar to all of us.

Q: Your portrayal of the Silken Folk is quite a bit different to most portrayals of the Fae. What’s with all the insects?

A; I wanted to draw on traditional aspects of fairytale, whilst adding elements of my own. The Silken Folk, who are shapeshifters, but can also appear as humans, is part of that: and it ties in with one of my favourite themes, which is that of perception. We look at the Silken Folk as we look at so many of the things that frighten or disturb us; sometimes from the tail of the eye; or some cases, not at all.

Q: The Lacewing King is such a difficult character. Spoilt and cruel and arrogant – why make him the hero?

A: He isn’t exactly the hero, but he does drive the story. As for his cruelty and arrogance, I needed a character who was capable of change over the course of the book. If I’d made him nice from the start, he wouldn’t have had such a long journey.

Coming June 3rd, 2021. Pre-order it here!

Read an early review of the book from Publishers Weekly!